Mastering Zcash

A Study in Private Money

With deep gratitude to Giulia Mouland for her feedback and editorial review, and to Arjun Khemani for his support.

Contributions to this article are more than welcome on GitHub through pull requests.

1. Introduction

Unless you’re using cash, the information about every purchase that you make is tracked and stored indefinitely. It doesn’t matter what it is, or how sensitive it is. The infrastructure that powers commerce, both offline and online, has effectively become an inescapable surveillance apparatus.

When it was first released, there were hopes that Bitcoin could fix this, but unfortunately, it hasn’t. In fact, contrary to many people’s understanding, Bitcoin is incredibly transparent, as every transaction ever made is permanently stored and visible to everyone. Sure, wallets are pseudonymous, but in order to receive BTC you need to provide your address, thus providing your entire transaction history and balance to the sender. On top of that, services like Arkham have made it trivial, for even the general public, to track and identify wallets.

This is why authorities condone Bitcoin, for to state actors, transparent chains are better than the digital currencies that they themselves control (often called Central Bank Digital Currencies or CBDCs) in many ways. Since there is no resistance from the population to using Bitcoin, and no oversight on how chain data is used by authorities, it offers perfect visibility for state actors to track everything, with full impunity.

In some ways, Bitcoin is actually worse than the banking system it sought to replace. At least bank records are private from the general public; Bitcoin isn’t.

It’s for this reason that Zcash takes a different approach: offering default privacy, rather than default transparency. This means that when you make a shielded Zcash transaction, the sender, the recipient, and the transaction amount are all encrypted. The network verifies the transaction is valid, verifying that you have the funds and aren’t spending more ZEC than you own, but isn’t privy to any information about the transaction itself.

Initially, when you think about it, this sounds impossible. How can you prove that something is true without revealing the thing that you’re proving? The answer is zero-knowledge proofs, specifically a construction called zk-SNARKs. The coverage of zk-SNARKs in this article will be kept light and accessible to the general reader, as it requires a substantial background in algebra and commitment schemes—beyond this article’s scope.

We will also cover Zcash’s origins in academic cryptography, the philosophy that shaped it, and the protocol as it exists today.

Some parts of this comprehensive study of Zcash will be more technical. Though I have tried to make things as clear and accessible as possible for everyone, if you have trouble with certain concepts, I recommend asking an LLM for clarification or simply skipping it and revisiting it later. If that doesn’t work, don’t hesitate to reach out with any questions.

2. Origins

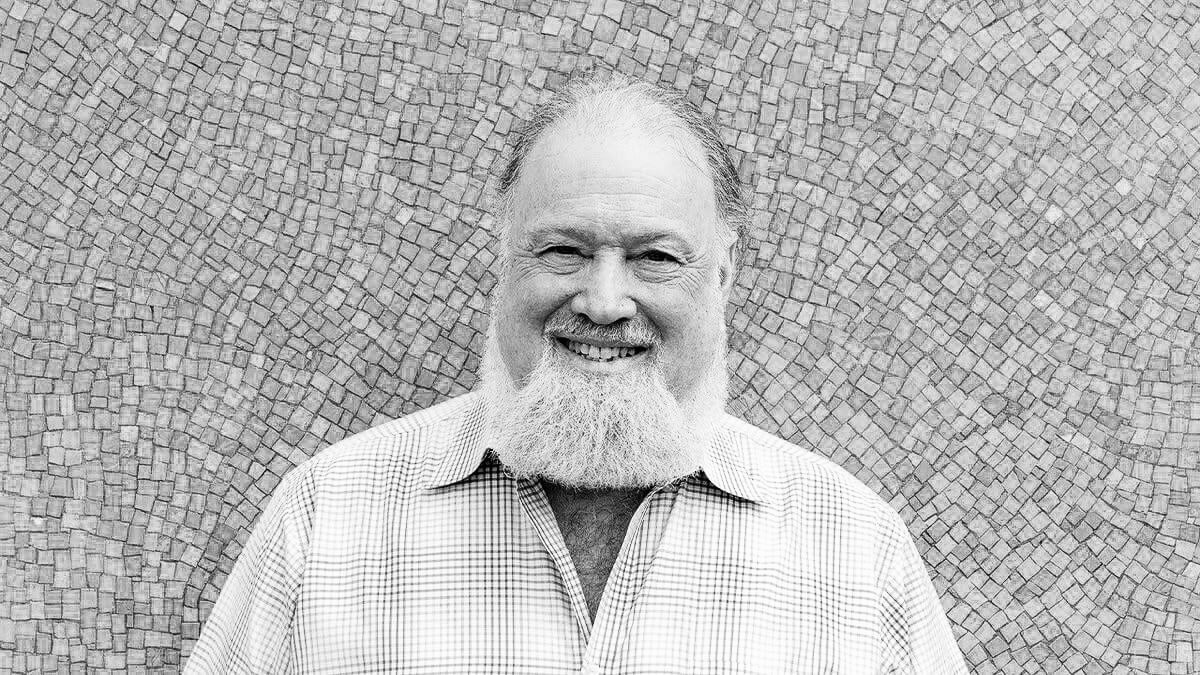

2.1 David Chaum and the Birth of Digital Cash

The idea of private digital money is far from new, in fact, it dates back to 1982. David Chaum, who was then a PhD candidate in computer science, published a paper titled “Blind Signatures for Untraceable Payments.”

The core insight of this paper was simple and elegant: a bank could sign a digital token without seeing its content, just as you could sign the outside of a sealed envelope. Then, when the token was spent, the bank could verify its validity through its own signature, but wouldn’t be able to link the spending to the withdrawal.

Later, in 1989, David Chaum founded DigiCash, a company built to commercialize this idea. The product was called ecash and it enabled users to withdraw digital tokens from their bank accounts and spend them at merchants without leaving a trail connecting the buyer to the purchase. Several banks piloted the technology, including Deutsche Bank and Credit Suisse.

Unfortunately, DigiCash didn’t succeed, the timing was wrong. Recall that this was created before widespread internet commerce, and before people understood the importance of online privacy. The company filed for bankruptcy in 1998, but with ecash, Chaum had proven that private digital money was doable.

2.2 The Cypherpunks

Soon after, a different kind of movement started taking shape. In 1992, a group of cryptographers, hackers, and libertarians started meeting in the San Francisco Bay Area and communicating via an electronic mailing list. They called themselves the cypherpunks.

The cypherpunks were not academics writing papers, they were ideologues writing code. Their founding premise was that in the digital age, privacy would not be granted by governments or corporations, instead, it would have to be built, deployed, and defended by individuals using cryptographic tools. In 1993, group member Eric Hughes crystallized this concept in A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto:

“Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age… We cannot expect governments, corporations, or other large, faceless organizations to grant us privacy out of their beneficence… We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any… Cypherpunks write code.”

The mailing list became a crucible for the ideas that would shape the next three decades of cryptographic development. Members included Julian Assange (before WikiLeaks), Hal Finney (who would later receive the first Bitcoin transaction), Nick Szabo (who proposed bit gold, a conceptual precursor to Bitcoin), and Wei Dai (whose b-money proposal was cited by Satoshi Nakamoto). In 1997, another member, Adam Back, invented Hashcash, the Proof of Work (PoW) system later adopted by Bitcoin.

The cypherpunks didn’t build a successful cryptocurrency, or did they? The creation of Bitcoin is attributed to the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, rumoured to have been a developer or a group of developers tied to the cypherpunks, and who has not been active in over a decade. In any case, what we know for sure, is that the cypherpunks built the culture, the tools, and the intellectual framework that has made private currency possible.

Shortly after this article was published, Zooko Wilcox, co-founder of Zcash, reached out noting the following:

- He was on the Cypherpunk mailing list! Meaning the cypherpunks did create a successful cryptocurrency. Mea culpa for that omission.

- Zooko became friends there with the founders, including Tim May who founded the crypto-anarachist movement, Eric Hughes who wrote A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto as previously mentioned, Bram Cohen who created the BitTorrent protocol and with whom he worked on a startup focused on chains of secure hashes, and John Gilmore who co-founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

- The cypherpunk mailing list was instrumental in his development, with John Gilmore, for example, becoming a friend, mentor, and inspiration.

2.3 Bitcoin: The Wrong Tradeoff

On October 31, 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto posted a paper to a cryptography mailing list titled “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.” The paper described a solution to a problem that had plagued digital currency designers for decades: how do you prevent double-spending without relying on a central authority?

Satoshi’s proposed answer was the blockchain: a public ledger maintained by a decentralized network of miners, secured by PoW; it was brilliant, and it worked! Bitcoin launched in January of 2009, and for the first time, people could transfer value over the internet without banks, intermediaries, or permission.

However, there was one glaring problem, as mentioned above, Bitcoin isn’t private. The blockchain is entirely public by design: every transaction, every address, and every balance are visible to anyone who’s interested. Satoshi acknowledged this problem in the paper, suggesting that users could preserve some of their privacy by using new addresses for each transaction, but this was weak mitigation, as addresses can be clustered, transaction graphs can be analyzed and real-world identities can be linked through exchanges, merchants, and metadata.

Nakamoto also later acknowledged that a privacy-preserving form of Bitcoin would enable a cleaner implementation of the protocol, but at the time, he couldn’t envision how to bring it about with zero-knowledge proofs.

Problematically, the privacy problem remained overlooked for years. Early Bitcoin users assumed pseudonymity was close enough to anonymity, but they were wrong. By the early 2010s, researchers demonstrated that blockchain analysis could de-anonymize users with high accuracy. Companies like Chainalysis, founded in 2014, turned this into a business by selling blockchain forensics to law enforcement agencies, exchanges, and even governments.

Bitcoin had solved the double-spend problem, but it had made the privacy problem worse.

2.4 Zerocoin: The Bolt-On Attempt

In 2013, Matthew Green, a cryptographer at Johns Hopkins University, and two graduate students, Ian Miers and Christina Garman, published “Zerocoin,” a paper proposing a solution to Bitcoin’s problem.

Their idea was to add a privacy layer on top of Bitcoin, such that users could convert their bitcoins into zerocoins, anonymous tokens with no transaction history. Later, when you wanted to spend it, you could convert it back to Bitcoin. The conversion process relied on cryptographic techniques known as zero-knowledge proofs, which let you prove that you owned a valid zerocoin without revealing its origin.

Zerocoin worked in theory, but it had problems. First, the proofs were large, two orders of magnitude larger than the few hundred bytes required for a normal Bitcoin transaction. Second, the cryptography was also limited: you could prove ownership, but you couldn’t hide transaction amounts. Third, and most critically, it required Bitcoin to adopt it as a protocol change, but Bitcoin’s conservative development culture made that unlikely.

The Bitcoin community debated Zerocoin and ultimately decided to pass on it. The proposal never made it into the protocol.

2.5 Zerocash: The Rebuild

In 2014, a new paper was published. The author list had expanded to include Eli Ben-Sasson and Alessandro Chiesa, cryptographers who had been working on a new generation of zero-knowledge proofs, plus Eran Tromer and Madars Virza.

The paper was titled “Zerocash: Decentralized Anonymous Payments from Bitcoin.” Despite what its title may lead you to think, it wasn’t simply a Bitcoin extension, it was a complete redesign.

The key innovation was the use of zk-SNARKs, which stands for Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge. These were zero-knowledge proofs that were small (a few hundred bytes), fast to verify (milliseconds), and expressive enough to prove complex statements about hidden data. With zk-SNARKs you can prove not just that you own a valid coin, but prove that an entire transaction is valid. This isn’t trivial, it means that the system verifies that the transaction amounts are correct, there is no double-spending, etc., all without revealing the sender, recipient, or amount.

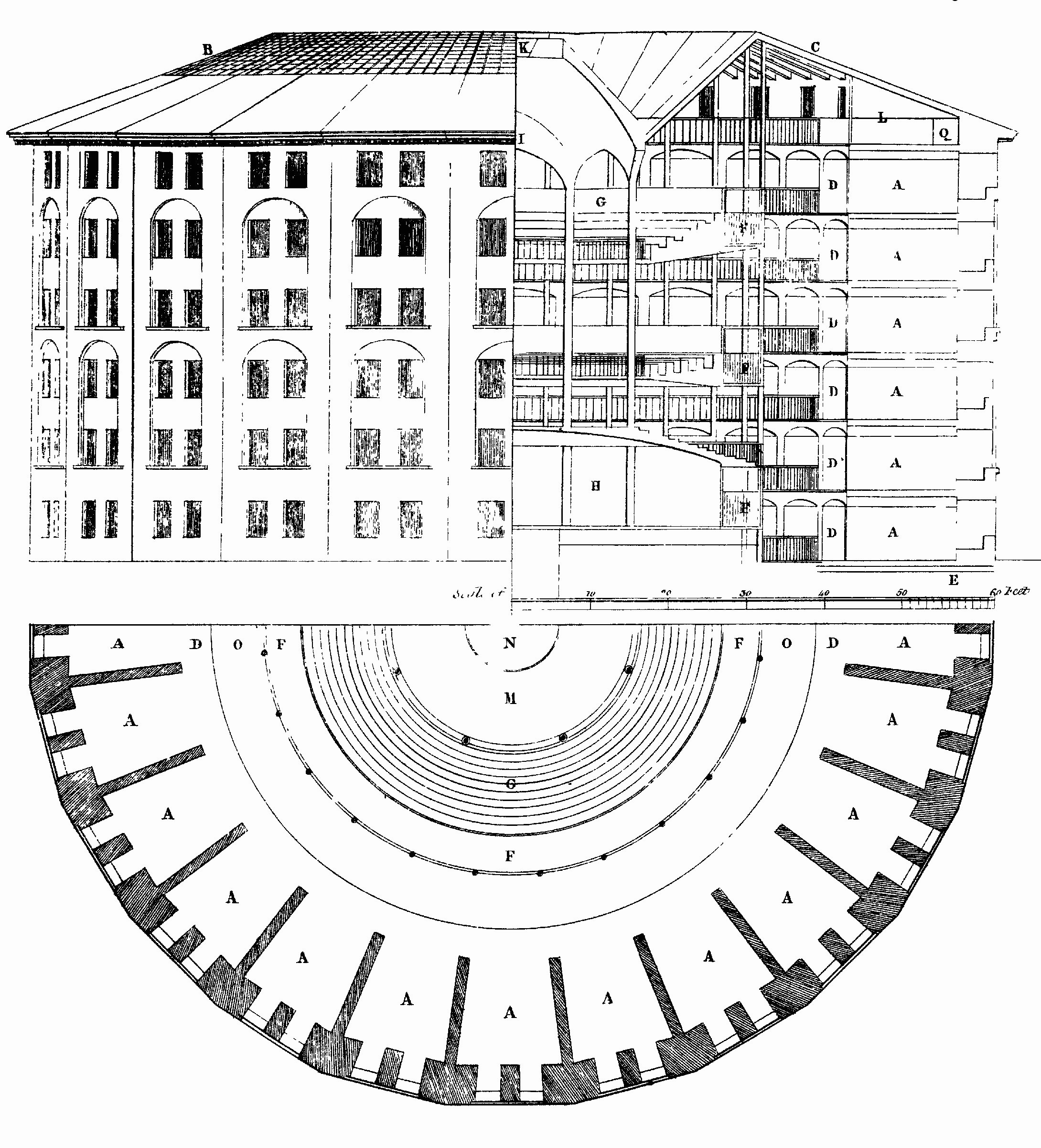

However, there was a catch: zk-SNARKs required a trusted setup. Someone had to generate a set of public parameters that the system would use forever, but, if that person kept the secret values used to generate the parameters, it’s so-called toxic waste, they could undetectably create counterfeit coins. Though this was of serious concern, the researchers believed it could be prevented with careful ceremony design.

2.6 The Genesis Block

Zooko Wilcox had been in the privacy and cryptography space for decades. He had worked at DigiCash in the 1990s and been involved with decentralized storage projects with strong privacy properties like Tahoe-LAFS. So, when the Zerocash paper was released, it was an immediate fit.

In 2016, Wilcox founded the Zcash Company, later renamed Electric Coin Company, and assembled a team to turn Zerocash into a production cryptocurrency. The academic authors mentioned above joined as advisors and collaborators on the project.

The trusted setup problem highlighted above required a creative solution. The team designed an elaborate, multi-party computation ceremony: six participants, all in different locations around the world, would contribute randomness to generate the public parameters, and as long as at least one participant destroyed their secret input, the toxic waste would be unrecoverable. The ceremony took place in late 2016, with participants including Peter Todd, a Bitcoin Core developer, and journalists who documented the process. Extensive work went into making sure that the ceremony wasn’t compromised, as outlined here.

On October 28, 2016, the Zcash genesis block was mined. For the first time, a production cryptocurrency offered genuine, cryptographic privacy. Thirty-four years after David Chaum’s first paper, the dream of untraceable digital money was running on a live network.

3. What is Zcash?

3.1 A Bitcoin Primer

Bitcoin is essentially a payment system with no central operator. There is no bank, no company, and no single server that can be pointed to. Its decentralized mechanism operates through thousands of computers around the world that maintain identical copies of a shared ledger, called the blockchain, and follow a set of rules to keep it in sync.

The blockchain is an append-only data structure, and it’s literally a chain of blocks, so you can add new entries (blocks), but you can never modify or delete old ones. Each new block consists of transactions made on the network at the time the block was created. Additionally, each block references the one preceding it, leading to the formation of a chain. If you wanted to change a transaction from the past, you’d have to rewrite every successive block, which becomes computational impossibility once enough time has passed. We will see why that is the case later.

Keys and Ownership

Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography for wallets. When you “create a wallet,” what you’re really doing is generating a key pair: a private key (a large random number, kept secret) and a corresponding public key (derived mathematically from the private key). A Bitcoin address is derived from a public key through hashing and encoding.

Here’s an example of what these look like in practice (abbreviated using ...):

- Private key:

1E99423A4ED27608A15...E6E9F3A1C2B4D5F6A7B8C9D0 - Public key:

03F028892BAD7ED57D2F...3A6A6C6E7F8C9D0A1B2C3D4E5F607182 - Bitcoin address:

1BoatSLRHtKNngkdXEeobR76b53LETtpyT

The private key lets you sign messages, while the public key lets anyone verify that a signature came from the corresponding private key without revealing the private key itself. This cryptography is what retains the private key’s privacy, as you can sign a message authorizing a transfer using your private key, and the network can verify your signature using your public key, without ever seeing your private key.

An important conclusion here is that this means wallets don’t “hold” BTC in any meaningful sense. There’s no file on your computer containing coins. Rather, the blockchain holds the record of which addresses control which outputs, and your wallet is just a signing tool, it stores your private keys and uses them to authorize transactions. If you lose your private keys, you lose access to your funds; not because the coins disappeared, but because you can no longer prove your ownership.

Transactions and UTXOs

Transactions are how Bitcoin value moves. When you send BTC, you’re publishing a signed message that effectively says: “I authorize the transfer of these coins to this address,” but what exactly are these coins?

Bitcoin doesn’t track balances, there aren’t database entries somewhere saying “Address X has 3.5 BTC.” Instead, Bitcoin uses Unspent Transaction Outputs, often abbreviated as UTXOs. Every transaction consumes existing outputs and then creates new ones. The outputs you control but haven’t yet spent are your UTXOs. This means that your “balance” is just the sum of all of your unspent outputs. There’s no running tally of coins, just a collection of discrete chunks you control.

Here’s a quick example: Imagine that you have a $20 bill and you want to buy a $12 item. Obviously, you can’t tear the bill in half, so you hand over the $20 and receive $8 in change.

UTXOs work the same way. If you own a 5 BTC output and want to send someone 3 BTC, you need to consume the entire 5 BTC output and create two new ones from it: 3 BTC for the recipient and 2 BTC that return to you as change. Your original 5 BTC output is now ‘spent’ and can never be used again.

As a result, a Bitcoin transaction is a data structure containing some metadata as well as:

- Inputs: References to UTXOs you’re spending, plus signatures proving you control them

- Outputs: New UTXOs being created, each locked to a recipient’s public key

Nodes validate that the inputs exist, haven’t been spent yet, and have valid signatures. If everything checks out, the transaction is relayed across the network and waits to be included in a miner’s block.

Here’s what a transaction looks like in practice (hashes and addresses are abbreviated using ...):

{

"txid": "c1b4e693...cbdc5821e3",

"inputs": [

{

"prev_txid": "7b1eabe...98a14f3f",

"output_index": 0,

"signature": "304402204e4...1a8768d1d09",

"pubkey": "0479be66...ffb10d4b8"

}

],

"outputs": [

{

"amount": 3.0,

"script": "OP_DUP OP_HASH160 89...ba OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG"

},

{

"amount": 1.99,

"script": "OP_DUP OP_HASH160 12...78 OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG"

}

]

}

Each input points to a previous transaction’s output by referencing its transaction ID and index, and each output specifies an amount. The signature proves you control the private key. The 0.01 BTC difference between the input of 5 BTC and outputs of 3BTC + 1.99 BTC, is the transaction fee, claimed by the miner.

Mining and Proof of Work (PoW)

Transactions don’t confirm themselves. They sit in a waiting area in a node called the mempool (memory pool) until a miner includes them in a block. Mining is the process by which new blocks get added to the chain, and it’s designed to be expensive. That’s a feature, not a bug, as we will see in a minute.

The problem solved by mining is: in a decentralized network with no central authority, who decides which transactions are valid? Who decides their ordering? If two conflicting transactions appear, say, someone tries to spend the same coins twice, who resolves this conflict?

Bitcoin’s solution is: in order to create a valid block, a miner must find a number, called a nonce, such that when the block header (containing the previous block’s hash, a timestamp, etc.) is combined with this nonce and hashed, the resulting hash is below a certain target value. Since cryptographic hashes are effectively random, there’s no way to find a valid nonce except by guessing, so miners guess billions of times per second.

For example, think of a block as a page of fixed information with one adjustable number on it (the nonce). Let’s assume we start counting the nonce at 0.

A computer turns the entire page into a single output number called a hash. A hash can be something like 6, or 03a5b20, ultimately it’s just a number (yes, 03a5b20 is a number, because it equals 3,824,416 in decimal). Remember that the nonce is the only adjustable number on the page, changing only the nonce produces a completely different hash (number) each time.

The network requires the hash to be below a fixed threshold value, and if it isn’t, the miner changes the nonce and tries again. Finally, the nonce is accepted when the hash meets the threshold requirement.

For example, imagine a case where the threshold value is 5. The miner has their page of information and starts with a nonce of 0. If the computer returns a 6, which is above 5, the miner tries again, now 1 as a nonce. If this time the computer returns a 4, which is below 5, then 1 is accepted as a nonce!

The difficulty adjusts every 2,016 blocks (about every two weeks), maintaining an average block time of ten minutes. If blocks are coming too fast, the target decreases, making the puzzle harder, and if blocks are coming too slow, the target increases. The difficulty adjustment is why Bitcoin’s block rate stays stable even as total mining power fluctuates.

Here’s what a block looks like:

{

"header": {

"version": 536870912,

"prev_block_hash": "0000000...de0e5c842",

"merkle_root": "8b30c5ba1...1e0d5f8a2c1",

"timestamp": 1701432000,

"target": "0000004f2c0...0000000",

"nonce": 2834917243

},

"transactions": [

{

"txid": "3a1b9c7e...7e8f9a0b1c",

"inputs": [{ "coinbase": "03a5b20...706f6f6c" }],

"outputs": [{ "amount": 6.25, "script": "OP_HASH160

f1c3...4c6a8 OP_EQUAL" }]

},

{ "txid": "c1b4e...5821e3" },

{ "txid": "7d5e8...b5c6d7e" }

]

}

The header is what gets hashed. Miners increment the nonce repeatedly until SHA256(SHA256(header)) < target, meaning until applying the SHA256 hash function twice on the header returns a hash below the target value. The first transaction is always the “coinbase” transaction, which creates new coins and pays the miner.

Once a miner finds a valid nonce, they broadcast the block and other nodes verify it, checking that the hash meets the target, that all transactions are valid, and that the miner didn’t create more coins than allowed. If valid, nodes append the block to their chain and begin working on the next one. The miner earns a block reward in the form of newly minted bitcoin, plus the transaction fees from the transactions included in the block.

So, how does this system prevent rewriting the past? Because each block’s hash is part of the next block, meaning that changing a single transaction changes the block’s hash and immediately breaks every block that comes after it.

5 and B’s hash is 6. If you change a transaction in A, now A’s hash has changed, and requires B’s hash to change as well. B’s hash takes into account A’s hash given that B comes after A and A’s hash is in B. So, B’s hash will no longer be 6 if a transaction is changed in A.In order to make the chain valid again, an attacker would have to redo the Proof of Work (the process of finding a nonce below a certain target value etc.) for not only that block, but for every subsequent block as well. Meanwhile, honest miners are mining and extending the “real” chain with new blocks. Additionally, Bitcoin follows the chain with the most cumulative Proof of Work, making it strongly inhibitive for attackers.

Therefore, a successful attack would require an attacker to have 51% of the mining power in order to eventually catch up with and become the ‘real’ chain. Mining power can also be referred to as hash power, as miners effectively just hash information countless times every second of every day.

The Transparency Tradeoff

Importantly, for this system to function without a central authority, everyone must be able to verify everything. Every node checks every transaction against the full history of the chain, every UTXO is tracked, and every signature is validated.

This comes at the cost of privacy, as every transaction and address balance is public. The entire flow of funds, from the 2009 genesis block to the most recently mined block, is visible to anyone who downloads the blockchain.

So, Bitcoin solved the problem of trustless digital money, but it didn’t solve the problem of trustless private digital money. That’s where Zcash comes in.

3.2 Bitcoin, But Private

Zcash is effectively like Bitcoin, but with the addition of encryption. In fact, many refer to it as encrypted Bitcoin, even though it’s a completely different cryptocurrency.

The economics of Zcash are nearly identical to Bitcoin’s, so if you understand Bitcoin’s monetary policy, you understand Zcash’s as well. Zcash has a hard cap of 21 million ZEC, just like Bitcoin has a 21 million BTC hard cap. New coins enter circulation through mining rewards, which halve approximately every four years, as with Bitcoin.

The consensus mechanism is also Proof of Work, though Zcash uses Equihash rather than Bitcoin’s SHA256-based system for mining. Something interesting about Equihash is that it was built with the explicit aim of resisting the specialized ASICs that dominate Bitcoin mining, therefore keeping mining accessible to people with consumer GPUs. The choice reflects Zcash’s early emphasis on decentralization, though it no longer works as Equihash ASICs now exist.

ASIC stands for Application-Specific Integrated Circuit, you can think of them as computers specifically designed to mine cryptocurrencies. There exist ASICs specialized in SHA256 mining, Equihash mining, etc.

ASICs hash information (blocks of transactions) all day long in hopes of finding a hash below the network’s target value.

Under the hood, Zcash uses the same UTXO transaction model as Bitcoin.

However, Zcash differs from Bitcoin in what you can do with the UTXOs. Bitcoin has one pool of funds: the public chain, whereas Zcash has several, split into the transparent pool and the shielded pools, but both pools use ZEC as currency, and you can move funds between them. The transparent pool works exactly like Bitcoin: addresses start with t, transactions are fully visible, and anyone can trace the flow of funds.

The shielded pools are completely different and are unique to Zcash. There are three pools , Sprout, Sapling, and Orchard, with Orchard being the newest and most advanced. Sprout and Sapling are now practically unused, since they date back to previous network upgrades and rely on trusted setups, which Orchard doesn’t; we will cover this further later on in the article. Shielded addresses start with z, and transactions reveal nothing about the sender, the recipient, or the amount.

The transparent pool exists for compatibility and optionality. Some users want auditability, some applications even require it, and exchanges often use transparent addresses for regulatory compliance. In this case, transparency is a feature, not a bug, and Zcash’s reliance on encryption for privacy in the shielded pool is unaffected by the usage of the transparent pools.

We should think of the transparent pool and the shielded pool as two entirely independent systems that do not affect each other. People often mistakenly criticize Zcash’s transparency feature as somehow decreasing its privacy, but that is false. The Zcash anonymity set is mathematically independent from how much ZEC sits in transparent addresses. So, even if 99% of ZEC were transparent, the privacy of the shielded 1% would only be determined by the shielded pool itself.

3.3 The Fundamental Problem

In Bitcoin, validating a transaction is straightforward. You check that the inputs exist and haven’t been spent before, that the signatures are valid, and that the outputs don’t exceed the inputs. Every piece of information needed to verify these conditions is right there on the blockchain, visible to everyone.

Such transparency is what makes Bitcoin trustless. You don’t need to trust anyone because you can verify everything yourself. If you wanted to, you could even run a node for maximal trustlessness. However, this is also what makes Bitcoin a surveillance tool, as the very data that enables verification is the same data that enables tracking.

Zcash wants both: trustless verification and privacy, but these seem to contradict each other. How can the network verify that a transaction is valid if it can’t see the transaction?

Think about what validation actually requires:

- The inputs exist, as you can’t spend coins that don’t exist.

- The inputs haven’t been spent before, so that there’s no double-spending.

- The authorization to spend, since you control the private key.

- The math works out, and outputs don’t exceed inputs.

In Bitcoin, nodes and miners check these four criteria by looking at the data. In Zcash, the sender, recipient, and amount are encrypted, and the data isn’t visible. How then can anyone check these criteria?

The answer is that Zcash doesn’t ask nodes and miners to check the data. Instead, the sender provides a zk-SNARK, a cryptographic proof, that demonstrates that the transaction is valid without revealing any of the underlying information. Miners and nodes don’t learn what the inputs are, who the recipient is, or how much is being transferred, they only learn one thing: the proof is valid, and therefore the transaction is valid.

It sounds insane, we can verify a financial transaction is valid, without seeing it!

The following sections explain why this is possible, including how Zcash represents value and tracks what is spent, as well as how zero-knowledge proofs tie everything together.

3.4 Shielded Notes

As mentioned above, Bitcoin uses UTXOs. Zcash’s shielded pool uses something conceptually similar called notes; you can think of notes as encrypted UTXOs.

So what is a note? A note is an encrypted object representing a specific amount of ZEC. It’s a discrete chunk of value, just like UTXOs, but unlike UTXOs, its contents are hidden. When you receive shielded ZEC, a note is created. When you spend the shielded Zec, that note is consumed and new notes are created for the recipient and your change if applicable, exactly as with UTXOs.

This is what an Orchard note looks like after decryption:

{

"addr": "u1pg2aaph7jp8rpf6...sz7nt28qjmxgmwxa",

"v": 150000000,

"rho": "0x9f8e7d6c5b4a...f8e7d6c5b4a39281706f5e4d3c2b1a0",

"psi": "0x1a2b3c4d5e6f70...c4d5e6f708192a3b4c5d6e7f809",

"rcm": "0x7a3b4c5d6e7b...d8e9f0a1b3d4e5f6a7b8c9d0e1f2a3b"

}

In this example, the value field v field shows 1.5 ZEC (150,000,000 zatoshis). The other fields, rho, psi and rcm will be covered later, for now, just understand that they are what makes the cryptography backing Zcash notes possible.

Notes are never modified, there is no updating of a balance. Rather, they’re created, they exist, and they’re destroyed when spent. If you have 10 ZEC and spend 3 ZEC, the original 10 ZEC note is consumed entirely, and two new notes are created: 3 ZEC given to the recipient and 7 ZEC returned to you, just like UTXOs.

The critical difference between Zcash’s notes and Bitcoin’s UTXOs is their visibility. A Bitcoin UTXO is public: everyone can see its value, when it gets spent, etc. A Zcash note is encrypted: only the owner, and anyone they share their viewing key with can see its contents. The blockchain stores a cryptographic commitment to the note, it does not store the note itself.

The blockchain never sees the decrypted note. In Orchard, each ‘action’ bundles together a spend and an output. Here’s what’s actually recorded:

{

"cv": "0x9a8b7c6d5...8d7e6f5a4b3c2d1e0f9a8b",

"nullifier": "0x2c3d4e5f6a7b...d2e3f48e9f0a1b2c3d",

"rk": "0x5e6f7a8b...5a6b7c8d9e0f1a2b3c4d5e6f",

"cmx": "0x1a2b3c4d5e6f7...d3e4f5a6b7c8d9e0f1a2b",

"ephemeralKey": "0x4d5e6f7a8b9...4f5a6b7c8d9e0f1a2b3c4d5e",

"encCiphertext": "0x8f7e6d5c4b3...a29180f7e6d5c",

"outCiphertext": "0x3c4d5e6f7a8...b9c0d1e2f3a4b5c"

}

As you can see, it’s all encrypted, we will go over the specifics of each field later.

You may be thinking, if notes are hidden, how does the network know they exist? Or how does it know when they’ve been spent? Here’s where commitments and nullifiers come in.

3.5 Commitments and Nullifiers

Zcash’s shielded pool faces two problems that Bitcoin solves trivially through transparency:

- Proving notes exist: When someone sends you shielded ZEC, how does the network know the note is real?

- Preventing double-spending: When you spend a note, how does the network know you haven’t spent it before?

The solution for Zcash is a combination of two cryptographic mechanisms: commitments and nullifiers.

Commitments

A commitment is a value computed by hashing the note’s fields together. Here’s what it looks like In Orchard:

cmx = Hash(addr, v, rho, psi, rcm) = 0x1a2b3c4d...9ca6b7c8d9e0f1a2b

‘Hash’ denotes the hashing function used. We take the fields of the shielded note, feed them to the hash function, and it returns a hash (in this case 0x1a2b3c4d...9ca6b7c8d9e0f1a2b).

There are two properties that make this useful:

- One-way: given the returned hash,

0x1a2b3c4d...9ca6b7c8d9e0f1a2b, you cannot recover the fieldsaddr,v,rho,psi, orrcm, and the content of the note is hidden. - Collision-resistant: you cannot find two different notes that produce the same commitment, each note maps to exactly one commitment.

Each time that a note is created, its commitment is added to the commitment tree — a Merkle tree — containing every note commitment ever created on the network.

A Merkle tree is a data structure that lets you prove that an item is in a large set without revealing the item or downloading the entire set.

Here’s how it works. Start with a list of values (in our case, note commitments): cm0 cm1 cm2 cm3

Pair them up and hash each pair together:

H0 = Hash(cm0, cm1)H1 = Hash(cm2, cm3)

Now you have two hashes. Pair and hash again:

root = Hash(H0, H1)

So far, we have taken pairs of items from the original set and combined each pair using a hash function. We then group the resulting hashes into pairs and hash them again, repeating this process layer by layer until we reach a single final hash. This final value is called the root hash, or Merkle root.

This root hash effectively summarizes the entire set:

root

/ \

/ \

H0 H1

/ \ / \

/ \ / \

cm0 cm1 cm2 cm3

The key property of Merkle trees is that if you change any leaf (commitment), meaning the values cm0, cm1, etc., every single hash above it changes too, all the way back to the root. The root acts as the fingerprint of the entire tree, if you have the same root, then you must have the same tree.

Additionally, Merkle proofs provide an efficient way to check for an item in the tree without having to check the whole tree.

For example, to prove that cm1 is in the tree doesn’t require revealing all of the commitments. To do so, just provide a Merkle path, that is, the sibling hashes along the way to the root. For cm1, the Merkle path is [cm0, H1].

Here’s how a verifier could check that:

- Take the first element in

[cm0, H1], meaningcm0, and hash it withcm1, the item we want to check, this gives usH0: Hash(cm0, cm1) = H0 - Hash the output of the first step (

H0) with the following item in[cm0, H1], meaningH1. This gives us theroothash:Hash(H0, H1) = root.

If the result matches the known root, then we can conclude that cm1 is in the tree, importantly, the verifier never sees cm2 or cm3, it’s not necessary for the verification.

The commitment tree contains every shielded note commitment ever created, equalling millions of leaves (commitments). So, when you spend a note, you prove (inside the zk-SNARK) that you know a commitment and the valid Merkle path to the current root, without revealing which commitment is yours.

The commitment tree is stored by nodes, as part of the chain state they maintain. Each block introduces new note commitments which nodes append to their local copy of the tree, updating the root accordingly.. The current root, known as the anchor, is what transactions reference when proving membership.

Nullifiers

Commitments may solve the existence problem, but they also create a new one: how do you prevent spending the same note twice?

In Bitcoin, this is trivial, because when you spend a UTXO, you directly reference its transaction identification and output index, such that everyone can see the UTXO has been spent. If you try to spend it again, nodes will reject the transactions because the UTXO has been marked as consumed.

The same is not possible for Zcash. If spending a note required pointing to its commitment, it would reveal which commitment you’re spending and link that note to all future transactions, thus breaching privacy.

In Zcash, the solution to prevent spending the same note twice is nullifiers. Nullifiers are values derived from a note, and can only be computed by the note’s owner.

Let’s say that the commitment tree has 1 million notes, and one of these notes is yours, specifically ‘commitment 0x1a2b...’

If spending the note required you to say “I’m spending 0x1a2b...” then:

Everyone knows that 0x1a2b... is yours, and it’s no longer just one of a million anonymous commitments. It’s tagged as belonging to whoever made this transaction, and though they don’t know what’s in that commitment, it’s still problematic that they know it’s yours.

Senders can now track you, as whoever created that note by sending you the ZEC knows the commitment they created. So, when you spend and point to it, they are able to observe that the payment has been spent, and learn when you moved your funds.

Over time, the spending may become linkable. An observer might be able to correlate transactions based on spending patterns, timing, and destination, such that your commitments get clustered together as “probably the same person.”

Nullifiers resolve these issues. If you publish the nullifier 0x2c3d..., which corresponds to the commitment 0x1a2b..., it’s impossible to compute the mapping of commitments to nullifiers without knowing your private key. The commitment remains anonymous in the Merkle tree, your spends cannot be linked, and the sender can’t tell if their payment was spent.

Here’s an example of a nullifier In Orchard:

nullifier = Hash(nk, rho, psi) = 0x2c3d4e5f6a7b...d2e3f48e9f0a1b2c3d

nk is the nullifier deriving key, a secret key only you possess. rho and psi are values from the note itself, as seen previously. No one else can compute this nullifier because no one else has your nk. Hash, as in previous examples, is the hashing function being used (we will cover this later).

Anytime that you spend a note, you also publish its nullifier. The network maintains a nullifier set, that is, a collection of every nullifier ever published. So, if a nullifier is already in the set, the transaction gets rejected, thus preventing double-spending.

Here’s how the nullifier set grows over time:

- Block 1000000:

nullifier set = { } - Block 1000001:

nullifier set = { 0x2c3d...3d } - Block 1000002:

nullifier set = { 0x2c3d...3d, 0x8f7a...2b } - Block 1000003:

nullifier set = { 0x2c3d...3d, 0x8f7a...2b, 0x1e4c...9a }

Each spend adds exactly one nullifier. The set cannot shrink, it only ever grows.

At the risk of being repetitive, let us cover once more why unlinkability is the critical property. The nullifier reveals nothing about which commitment it corresponds to. An observer sees a nullifier appear and knows that some note was spent, but can’t tell which one. The commitment tree could contain millions of notes and the nullifier could correspond to any of them.

Putting it all together

Given that commitments are never deleted, as the commitment tree is append-only and grows indefinitely, commitments remain in the tree even after a note is spent.

This is precisely what makes Zcash’s anonymity set so strong. Spending requires proving “I know one of the N million commitments in this tree” without revealing which one. The spent note’s commitment is mixed among the others, so that even if an observer sees a nullifier appear they could not narrow down which of the millions of commitments it corresponds to.

Your privacy set includes every shielded note ever created on the network.

To summarize, every shielded transaction involves:

- Creating notes, which adds new note commitments to the commitment tree.

- Spending notes, which publishes and adds a nullifier to the nullifier set.

In order to construct a transaction, you must provide a zk-SNARK that proves:

- You know a note with a commitment in the tree, via a valid Merkle path.

- You know the secret key needed to compute that note’s nullifier.

- The nullifier you’re publishing corresponds to that note.

- The amounts balance of the entire transaction; inputs equal outputs plus fee.

The network verifies the proof, checks whether or not the nullifier is in the set, and accepts the transaction. Importantly, it never learns which commitment was spent, who sent funds to whom, or how much was transferred.

3.6 Keys and Addresses

Bitcoin has a simple key model: one private key, one public key, and one or more addresses. Zcash’s shielded system is more complex, as different operations require different levels of access. Zcash leverages a hierarchy of keys to address this complexity.

The Spending Key

The spending key (sk) is your master secret, it’s a very long and random number of 256 bits. Whoever has this can spend your funds, as everything else is derived from the spending key.

The Full Viewing Key

The full viewing key (fvk), derived from the spending key, lets you see everything about your wallet’s activity: incoming payments, outgoing payments, amounts, and memo fields, but it cannot handle spending.

The full viewing key is useful for cases where you want to grant someone audit access without giving them control. Through the viewing key an accountant could verify your transaction history, a business could let compliance review its books, or a tax authority could confirm reported income; all without risking that the auditor walks away with the funds.

Incoming and Outgoing Viewing Keys

The full viewing key can also be split into its constituent elements:

Incoming viewing key (ivk), which lets you detect and decrypt notes sent to you, but not notes that you’ve sent to others.

Outgoing viewing key (ovk), which lets you decrypt the outgoing ciphertexts, so that you can see what you’ve sent and to whom.

This granularity exists because users may want to share only limited information. For example, if you want to provide a service with your incoming viewing key so the service can notify you of received payments, without revealing any information about your spending patterns.

A wallet can also choose to make sent note details unrecoverable, even to holders of the full viewing key. It does this by using a random OVK at the time of sending and immediately zeroing it from memory. The outCiphertext is then encrypted to a key that no one possesses, making it impossible to determine the recipient address from the FVK alone. The value can still be inferred by subtracting the change from the input total, but the destination is lost.

The Nullifier Deriving Key

The nullifier deriving key (nk), also derived from the spending key, is used to compute nullifiers when spending. This is required in order to mark notes as spent, which is why viewing keys alone can’t authorize transactions—they don’t have access to nk.

Addresses

At the bottom of the hierarchy are the addresses: what you give to people so they can pay you. In Orchard, addresses are derived from the incoming viewing key using a diversifier, which is just a small piece of random data. This means that even an IVK-only merchant terminal can derive new diversified addresses without needing the full viewing key or spending authority.

The diversifier enables diversified addresses, meaning you can generate billions of unlinkable addresses from a single wallet. Though each address is completely different, they all funnel to the same set of keys. Additionally, you can give a unique address to every person or service you interact with.

Say you receive payments from an employer, a client, and an exchange. You give each a different diversified address:

- Employer pays to:

u1employer8jp8rpf6...qjmxgmwxa - Client pays to:

u1clientaph7jp8rpf...sz7nt28qj - Exchange pays to:

u1exchng2aaph7jp8...gmwxasz7n

The three addresses belong to you and your wallet receives each sender’s incoming payments, but the employer, client, and exchange cannot deduce that they’re paying the same user by comparing their addresses.

The Key Hierarchy

Here’s the hierarchy:

spending key (sk)

|

+---> full viewing key (fvk)

| |

| +---> incoming viewing key (ivk)

| |

| +---> outgoing viewing key (ovk)

| |

| +---> addresses (via diversifiers)

|

+---> nullifier deriving key (nk)

As you move down the hierarchy, each level reveals less information. The spending key can do everything, the full viewing key sees everything, but can’t spend, and the incoming viewing key only sees incoming funds. Lastly, addresses reveal nothing, they’re just destinations.

4. Transaction Lifecycle

This chapter will cover exactly what happens when you send shielded ZEC, from the moment you hit ‘send’ to the moment the recipient sees their balance update. To exemplify this, we’ll follow every stage of a single transaction, examining what your wallet computes, what the network sees, and what ends up on the blockchain.

4.1 The Setup

Alice wants to send 5 ZEC to Bob. She opens her wallet, enters Bob’s shielded address, specifies the amount, and confirms the send. What happens next involves each of the mechanisms we’ve covered thus far: notes, commitments, nullifiers, keys, Merkle proofs, and zk-SNARKs.

Alice’s wallet holds two unspent notes:

- Note A: 3 ZEC

- Note B: 4 ZEC

She’ll spend both (7 ZEC total) to send Bob 5 ZEC, pay a 0.001 ZEC fee, and receive 1.999 ZEC in change.

4.2 Note Selection and Retrieval

Remember, Alice’s wallet doesn’t actually store ZEC, it stores the information needed to spend notes: the decrypted note data and the keys that control them. When Alice synced her wallet, it scanned the blockchain, attempted to decrypt every shielded output using her incoming viewing key, and stored the ones that succeeded.

Here’s an example of note A:

{

"addr": "u1alice...",

"v": 300000000, // 3 ZEC in zatoshis

"rho": "0x7a8b9c...",

"psi": "0x1d2e3f...",

"rcm": "0x4a5b6c...",

"position": 847291, // Position in commitment tree

"cmx": "0x9f8e7d..." // The commitment

}

The position field is crucial because it tells the wallet where in the commitment tree this note is situated, information necessary to construct the Merkle proof.

4.3 Merkle Paths

In order to spend a note, Alice must prove that its commitment exists in the tree, without revealing which commitment it is. This requires proving a Merkle path from the commitment to the root.

Alice’s wallet maintains Merkle witnesses locally as it syncs the blockchain, updating them as new commitments are appended to the tree. This is critical: querying a full node for a Merkle path at a specific position would reveal which note is being spent, which would be a serious privacy leak. Full nodes don’t even maintain the entire note commitment tree—only recent frontiers and the set of valid anchors.

For Note A, at position 847,291 in a tree with depth 32, the path consists of 32 sibling hashes:

merkle_path_A = [

"0x1a2b3c...", // Sibling at level 0

"0x4d5e6f...", // Sibling at level 1

... // 30 more siblings

"0x7g8h9i..." // Sibling at level 31

]

Anyone with access to this path can verify that cmx_A is in the tree by hashing back to the root. but, inside the zk-SNARK, Alice can prove this without revealing cmx_A or the path itself.

The wallet also records the anchor—the Merkle root at the time the witness was captured. The transaction will reference this anchor and nodes can use it to verify that it’s a valid root.

4.4 Computing Nullifiers

Alice has her notes and their Merkle paths, now she needs to mark them as spent.

Recall from section 3.5 that nullifiers solve the fundamental problem of preventing double-spending without revealing the note being spent? With Bitcoin, you have to point to a UTXO directly and everyone can see it’s now consumed, but with Zcash, pointing to a commitment would destroy privacy by linking you to that specific note.

Alice computes a nullifier for each note she’s spending, the nullifier is derived from the note’s data and her secret nullifier deriving key (nk):

nullifier_A = Hash(nk, rho_A, psi_A) = 0x2c3d4e5f...

nullifier_B = Hash(nk, rho_B, psi_B) = 0x8f7a9b2c...

The rho and psi values are unique to each note, meaning they were set when the note was created. The nk is derived from Alice’s spending key, but only she possesses it.

The construction has two critical properties:

It’s deterministic: Each note produces exactly one nullifier. If Alice tried to spend Note A twice, she’d have to publish

0x2c3d4e5f...twice. The network maintains a nullifier set of every nullifier ever published, so the second attempt would be rejected because that nullifier already exists.It’s unlinkable: No one else can compute the nullifier for Alice’s notes because no one else has her nk, and crucially, no one can work backwards from a nullifier to determine its corresponding commitment. So, when

0x2c3d4e5f...appears on the blockchain, observers will see that some note was spent, but won’t be able to tell which of the millions of commitments in the tree it came from.

The nullifiers will be included in Alice’s transaction and published on-chain, but are the only public trace of her spending. Just two opaque 32-byte values that reveal nothing about the notes themselves, their amounts, or who controlled them.

4.5 Creating Output Notes

Alice is spending 7 ZEC (3 ZEC + 4 ZEC) and needs to create two new notes: 5 ZEC for Bob and 1.999 ZEC for her change; there’s a 0.001 ZEC transaction fee.

Each note requires novel randomness, so Alice’s wallet generates the cryptographic components that make each note unique and spendable only by its intended recipient.

Generating Note Components

For Bob’s 5 ZEC note:

{

"addr": "u1bob...", // Bob's shielded address

"v": 500000000, // 5 ZEC in zatoshis

"rho": "0x3e4f5a6b...", // Derived deterministically

"psi": "0x7c8d9e0f...", // Random

"rcm": "0x1a2b3c4d..." // Random (commitment randomness)

}

For Alice’s 1.999 ZEC change note:

{

"addr": "u1alice...", // Alice's own address

"v": 199900000, // 1.999 ZEC in zatoshis

"rho": "0x5f6a7b8c...",

"psi": "0x9d0e1f2a...",

"rcm": "0x4e5f6a7b..."

}

The rho value in Orchard is derived deterministically from the transaction, which prevents against certain types of cryptographic attacks. The psi and rcm values are freshly sampled random numbers. Together, these values ensure that even if Alice sends Bob 5 ZEC a thousand times, the note’s commitment would be different every time.

Computing Commitments

Once the note components are ready, Alice computes the commitment for each output:

cmx_bob = Hash(addr_bob, 500000000, rho_bob, psi_bob, rcm_bob)

= 0x8a9b0c1d...

cmx_alice = Hash(addr_alice, 199900000, rho_alice, psi_alice, rcm_alice)

= 0x2d3e4f5a...

These commitments are what will be published on-chain and added to the commitment tree. They reveal nothing about the notes themselves, they are opaque 32-byte hashes, but anyone who knows the underlying values (the recipient, specifically), can verify that a commitment corresponds to a specific note.

Encrypting the Notes

The commitments go on-chain, but Bob needs the actual note data in order to later spend his 5 ZEC. He needs to know the value, rho, psi, and rcm, as without these, the commitment is useless as he can’t construct a valid nullifier or prove ownership.

Alice encrypts each note so that only the intended recipient can read it:

For Bob: Alice uses Bob’s address (which contains his public key material) to encrypt the note. The result is the encCiphertext ciphertext: a blob of encrypted data that can only be decrypted using Bob’s incoming viewing key. When Bob’s wallet scans the blockchain and successfully decrypts this ciphertext, he learns he received 5 ZEC and stores all the data needed to spend it.

For Alice’s records: There’s a second ciphertext called outCiphertext: this one is encrypted to Alice’s outgoing viewing key, allowing her wallet to remember what she sent. Without this, Alice wouldn’t have a record of where her funds went. It’s encrypted, rather than being stored in plaintext, so that node operators and observers can’t read it.

{

"cmx": "0x8a9b0c1d...",

"ephemeralKey": "0x6b7c8d9e...",

"encCiphertext": "0x9f8e7d6c5b4a...[512 bytes]...",

"outCiphertext": "0x3c4d5e6f7a8b...[80 bytes]..."

}

The ephemeralKey is a one-time public key generated for this specific encryption, and Bob can use it alongside his private key in order to decrypt encCiphertext. This is standard for public-key encryption, but the twist is that it’s happening inside a system which never linked Bob’s address to an identity, and where the ciphertext doesn’t reveal anything to outside observers.

At this point, Alice has everything required for the outputs: two commitments to publish and encrypted payloads so that each recipient can claim their note. Now comes the hard part: proving it’s valid without revealing any of it.

4.6 The Proof

Alice has assembled all of the pieces: the two notes to spend, their Merkle paths, the nullifiers that will mark them as consumed, and two fresh output notes with their commitments and encrypted payloads. Now, how to convince the network that everything is valid without revealing the details?

Here’s where zk-SNARK comes in.

What the Proof Demonstrates

The proof is a cryptographic object that demonstrates all of the following are true:

The input notes exist. Alice knows two of the commitments that are in the commitment tree. She proves this when outlining the valid Merkle paths from those commitments to the anchor (the tree root). The proof doesn’t reveal which commitments Alice is referencing, just that they’re in there somewhere among the millions.

Alice controls the inputs. Alice knows the spending keys for both notes, specifically, she knows the secret values needed to derive the nullifiers and authorize the spend. Without this, anyone could try to spend anyone else’s notes.

The nullifiers are correct. The nullifiers that she’s publishing actually correspond to the notes she’s spending. Alice can’t publish arbitrary nullifiers, they must be derived from real notes she controls using the proper formula.

The transaction amounts balance. The sum of the input values (3 + 4 = 7 ZEC) equals the sum of the output values (5 + 1.999 = 6.999 ZEC) plus the fee (0.001 ZEC). No ZEC is created or destroyed. This is the fundamental conservation law of the system.

The output commitments are well-formed. The commitments she’s publishing for Bob’s note and her change note are correctly computed from valid note data. She can’t publish garbage commitments—they must follow the proper structure.

The network doesn’t learn which notes were spent, who the recipient is, or the amount that moved from one party to another. It only learns that someone made a valid transaction: real inputs, real outputs, correct math, and proper authorization. That’s enough to update the global state, meaning adding commitments and recording nullifiers, without knowing anything about the transaction itself.

What the Proof Actually Is

After all of this complexity, the proof itself is almost anticlimactic: roughly one to two kilobytes of data - that’s it! It’s just a small blob of bytes that encodes a mathematical argument.

Verification is fast, just a few milliseconds on modest hardware. A node receives the proof, runs the verification algorithm, and returns a binary answer: valid or invalid. No judgment calls, no heuristics, no probabilistic guesses; the math either checks out or it doesn’t.

This asymmetry is zk-SNARKs’ magic. Creating the proof is computationally expensive, Alice’s wallet does real work, crunching through elliptic curve operations and polynomial math. However, verifying the proof is cheap. The asymmetry makes the system practical: every node on the network can verify every shielded transaction without re-doing the heavy computation.

The Circuit

How does Alice actually produce this proof? By running her transaction data through something called a circuit—a formal specification of exactly what conditions must hold for a valid Orchard spend.

Think of the circuit as a massive checklist encoded in mathematical constraints. The step to prove “the Merkle path must be valid” becomes a series of hash computations that must produce the right output, the step “the nullifier must be correctly derived” becomes constraints on how certain values relate to each other, finally “the amounts must balance” becomes an equation that must hold.

Alice’s wallet takes her private inputs (notes, keys, paths, randomness) and grinds through this circuit to find values that satisfy every constraint. The zk-SNARK machinery then compresses this entire satisfying assignment into a tiny proof that anyone can check.

Alice’s wallet has now produced a proof: a ~1.5 KB object asserting that a valid transaction exists, without saying what it is. Now it’s time to package everything up and send it to the network.

4.7 Assembling the Transaction

Alice has her nullifiers, her output notes, her encrypted payloads, and her proof - now she needs to package everything into a transaction that the network can process.

The Action Structure

Orchard uses a structure called an action. Each action bundles exactly one spend and one output together, this is a deliberate design choice. Earlier Zcash protocols (Sprout and Sapling), separated spends and outputs, but this leaked information about transaction structure. If you saw a transaction with three spends and one output, you would be learning something. Orchard eliminates this problem by forcing a 1:1 pairing.

Alice is spending two notes and creating two outputs, so her transaction contains two actions:

- Action 0: Spends Note A (3 ZEC), creates Bob’s note (5 ZEC)

- Action 1: Spends Note B (4 ZEC), creates Alice’s change note (1.999 ZEC)

The pairing within each action is arbitrary. Action 0 doesn’t mean Note A “became” Bob’s 5 ZEC. The values don’t match, and that’s fine. What matters is the global constraint: total inputs equal total outputs plus fee. The action structure just ensures tat observers can’t infer transaction shape.

What Goes Onchain

Here’s what Alice’s transaction actually contains:

{

"anchor": "0x7f8e9d0c...",

"actions": [

{

"cv": "0x9a8b7c6d...",

"nullifier": "0x2c3d4e5f...",

"rk": "0x5e6f7a8b...",

"cmx": "0x8a9b0c1d...",

"ephemeralKey": "0x6b7c8d9e...",

"encCiphertext": "0x9f8e7d6c...[580 bytes]",

"outCiphertext": "0x3c4d5e6f...[80 bytes]"

},

{

"cv": "0x1b2c3d4e...",

"nullifier": "0x8f7a9b2c...",

"rk": "0x4d5e6f7a...",

"cmx": "0x2d3e4f5a...",

"ephemeralKey": "0x8c9d0e1f...",

"encCiphertext": "0x7e8f9a0b...[580 bytes]",

"outCiphertext": "0x5a6b7c8d...[80 bytes]"

}

],

"proof": "0x1a2b3c4d...[~1.5 KB]",

"bindingSig": "0x4e5f6a7b...[64 bytes]"

}

Let’s break this down:

anchor: The Merkle root that Alice’s proof references. This commits her transaction to a specific state of the commitment tree. Nodes will verify this is a valid root that existed at some point in the tree’s history. While old anchors are technically valid, wallets typically use recent anchors to maximize the anonymity set.

cv (value commitment): A cryptographic commitment to the value being spent or created in each action. These don’t reveal the actual amounts. Instead, they’re constructed so that the sum of all cv values across the transaction encodes the net flow. If the transaction is balanced (inputs = outputs + fee), the math works out. If not, verification fails.

nullifier: The nullifiers for Note A and Note B. These get added to the nullifier set, marking those notes as spent forever.

rk (randomized verification key): This is used to verify the spend authorization signature. This proves Alice authorized this specific transaction without revealing her actual spending key.

cmx: The commitments for Bob’s note and Alice’s change note. These get added to the commitment tree.

ephemeralKey + encCiphertext + outCiphertext: The encrypted note data, as covered in section 4.5. These don’t affect consensus, but without them, recipients couldn’t claim their funds.

proof: The zk-SNARK proving everything is valid. One proof covers the entire transaction (both actions).

bindingSig: A signature that ties all the pieces together. It proves that the cv values across all actions sum correctly (guaranteeing value conservation) and that the transaction hasn’t been tampered with. This is the final check that the amounts actually balance.

The Fee

You’ll notice the fee isn’t explicitly stated anywhere, that’s because it’s implicit. Alice’s input total is 7 ZEC and her output total is 6.999 ZEC. The difference, 0.001 ZEC, is the transaction fee, which is claimed by miners.

The value commitments encode net flow, so when a miner verifies the binding signature, they’re confirming that inputs minus outputs equals the claimed fee. If Alice tried to claim her outputs totaled 7 ZEC, leaving no fee, the binding signature would fail. If she tried to create extra ZEC out of thin air and claimed 8 ZEC of outputs from the 7 ZEC of inputs, the proof itself would be invalid.

The fee is public. Observers can see how much was paid to process the transaction, but that’s the only visible value. The input amounts, output amounts, and transfer of value between parties remain hidden.

Importantly, ZIP 317 standardizes fee calculations so that compliant wallets do not permit discretionary fee amounts. This matters for privacy: if wallets allowed arbitrary fees, the choice of fee would leak information that could help fingerprint transactions or distinguish between wallet implementations.

4.8 Broadcasting and Mempool

Alice’s wallet has assembled the complete transaction, now it needs to reach the network.

Sending to the Network

The sending process proceeds as follows. Alice’s wallet connects to one or more Zcash nodes and broadcasts the transaction. The message propagates through the peer-to-peer network, hopping from node to node until it reaches the miners and the broader network. The sending process works exactly as in Bitcoin, the transaction is just data gossiped from nodes to peers.

From Alice’s perspective, this takes one or two seconds. She sees “transaction broadcast” in her wallet and just waits for the confirmation.

Initial Validation

When a node receives Alice’s transaction, it doesn’t blindly accept it. Before relaying it further or adding it to the mempool, the node runs a series of checks:

Proof verification: The node runs the zk-SNARK verifier on Alice’s proof. This takes a few milliseconds. If the proof is invalid, the transaction is rejected immediately. No further checks needed.

Anchor check: The node verifies that the anchor Alice used (the Merkle root her proof references) is a valid root from the commitment tree’s history. The consensus protocol does not prohibit old anchors—any anchor that was ever a valid tree root is accepted. However, using a recent anchor is strongly advisable because it maximizes the anonymity set: the more notes in the tree at the time of the anchor, the larger the crowd Alice’s note hides in. Some wallets, like YWallet, allow selection of older anchors to enable spending old notes without requiring the wallet to have scanned all subsequent blocks.

Nullifier check: The node checks both nullifiers against its local nullifier set. If either

0x2c3d4e5f...or0x8f7a9b2c...already exists in the set, Alice is attempting to double-spend. The transaction is rejected.Structural validity: The node confirms the transaction is well-formed: correct field lengths, valid encodings, binding signature verifies, and so on. Malformed transactions are dropped.

If all of the checks pass, the node considers the transaction valid. Then, it adds the transaction to its mempool (memory pool), a holding area for unconfirmed transactions, and relays it to other nodes.

Waiting in the Mempool

The mempool is purgatory for transactions. Alice’s transaction sits there alongside hundreds or thousands of others, all waiting for a miner to pick them up and include them in a block.

Miners select transactions from the mempool based on fees. Higher fee transactions generally get picked first. Alice paid 0.001 ZEC, which is typical for Zcash, and under normal network conditions, this is enough to get included in the next block or two.

During the waiting period, Alice’s transaction is unconfirmed. The network has validated it, but it hasn’t been written into the blockchain yet. Bob’s wallet might detect the pending transaction - some wallets show incoming unconfirmed transactions - but he can’t spend those funds until the transaction is mined.

The transaction is broadcast. Nodes have validated it. Now, Alice waits for a miner to do the final work.

4.9 Block Inclusion and Finality

A miner selects Alice’s transaction from their mempool, bundles it with other transactions, and begins the work of mining a new block.

Mining the Block

Zcash uses Proof of Work, just like Bitcoin. The miner constructs a block header containing the previous block’s hash, a timestamp, a Merkle root of the included transactions, and a nonce. Then, they grind through nonces until finding one that produces a hash below the target difficulty.

This process is identical to what we covered in the Bitcoin primer (section 3.1), with one exception: Zcash uses the Equihash algorithm instead of SHA256. The security properties are the same - finding a valid block requires significant computational work and verifying that work is trivial.

When a miner finds a valid nonce, they broadcast the block and then other nodes verify it: valid proof of work, valid transactions, correct structure. If everything checks out, nodes append the block to their chain and Alice’s transaction becomes part of the permanent record.

State Updates

Once the block is accepted, the network’s state changes:

The commitment tree grows: Bob’s note commitment

0x8a9b0c1d...and Alice’s change note commitment0x2d3e4f5a...are appended to the commitment tree. Now the tree now contains two more leaves than before and a new Merkle root is computed. This root becomes a valid anchor for future transactions.The nullifier set expands: Alice’s two nullifiers (

0x2c3d4e5f...and0x8f7a9b2c...) are added to the nullifier set. Those notes are now permanently marked as spent. Any future transaction attempting to use either nullifier will be rejected.The block reward is issued: The miner receives newly minted ZEC (the block subsidy) plus the sum of all transaction fees in the block, including Alice’s 0.001 ZEC.

These state updates are deterministic. Every node that processes the block arrives at exactly the same new state. The commitment tree has the same new root everywhere. The nullifier set contains the same entries everywhere. This is what makes the network consistent without central coordination.

Confirmations

Alice’s transaction is now confirmed, but confirmation doesn’t mean finality.

Like Bitcoin, Zcash uses pure Proof of Work, which has no cryptographic finality. The chain with the most cumulative work wins, but nothing prevents a sufficiently resourced attacker from building a longer chain that rewrites history. Transactions in orphaned blocks return to the mempool or become invalid if they conflict with the attacker’s chain.

The conventional wisdom—that after six confirmations, reversal is “negligible”—is misleading. It frames security as a statistical property when it’s actually an adversarial one. This applies to all pure-PoW chains, Bitcoin included. Against an attacker with majority hashpower, no confirmation count provides cryptographic certainty—only economic assumptions about attacker incentives and hashpower costs.

The transaction is mined and the state is updated. Alice’s old notes are gone forever, replaced by two new notes in the commitment tree. One belongs to Bob, and now he needs to find it.

4.10 Recipient Detection

Alice’s transaction is on-chain. Bob’s 5 ZEC exists as a commitment in the tree, but Bob doesn’t know that yet. His wallet needs to find the corresponding note.

Scanning the Blockchain

Bob’s wallet periodically syncs with the network, downloading new blocks and scanning for incoming payments. The challenge is that Bob can’t simply search for his address. Shielded outputs don’t contain addresses in plaintext, every output resembles random encrypted data.

Bob’s wallet tries to decrypt every shielded output it encounters, so for each encCiphertext of every action of every block, the wallet attempts decryption using Bob’s incoming viewing key. Most of these attempts fail and produce unusable data, but that’s expected since those outputs belong to someone else.

Finally, when Bob’s wallet hits Alice’s transaction and tries to decrypt the ciphertext in Action 0, the decryption succeeds and the valid note data emerges.

Recovering the Note

When decryption works, Bob’s wallet recovers the full note plaintext:

{

"addr": "u1bob...",

"v": 500000000,

"rho": "0x3e4f5a6b...",

"psi": "0x7c8d9e0f...",

"rcm": "0x1a2b3c4d..."

}

Bob now has everything he needs:

The value: 5 ZEC (500,000,000 zatoshis). His wallet updates his balance accordingly.

The note components: The

rho,psi, andrcmvalues that Alice generated. These are essential. Without them, Bob couldn’t compute the commitment to verify that it matches what’s on-chain, or derive the nullifier to spend the note later.The position: Bob’s wallet also records where this commitment sits in the tree. When the block was processed, the commitment was appended at a specific leaf index. Bob needs this position to construct a Merkle path when he eventually spends.

Verifying the Note

Bob’s wallet doesn’t blindly trust the decrypted data. It recomputes the commitment from the recovered values:

cmx_check = Hash(addr_bob, 500000000, rho, psi, rcm)

If cmx_check matches the cmx published onchain in Alice’s transaction, the note is valid. If they don’t match, something is incorrect (either corruption or malicious senders), and the wallet discards the note.

During normal operations, this check always passes. Alice’s wallet constructed the note correctly, and the decryption recovered exactly what she encrypted.

A Spendable Note

Bob now owns a spendable 5 ZEC note. His wallet stores the note data locally and keeps it ready for whenever he wants to use it. At that point, he’ll follow the same process that Alice did in order to send it to him:

- Select the note

- Retrieve its Merkle path from the locally maintained witnesses

- Compute its nullifier

- Create output notes for his recipients

- Generate a proof

- Broadcast the transaction

The cycle repeats: Bob’s spend will reveal a nullifier, marking his note as consumed, new commitments will be added to the tree, and then new recipients will scan, decrypt, and discover their funds.

Alice sent 5 ZEC to Bob. The network verified the transaction without learning who sent what to whom, but Bob was still able to detect his payment without anyone else knowing he received it. The transaction is complete.

5. The Philosophy of Privacy

5.1 Privacy as a Precondition for Progress

Privacy does not mean secrecy, for secrecy aims to hide something shameful. Privacy is the right to choose what you reveal and to whom. Privacy is autonomy over your own information, it’s the foundation of freedom itself.

This distinction matters because critics of privacy often conflate the two. The refrain of authoritarian systems proclaims that “if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear,” and assumes that privacy is only valuable to those with something to conceal. However, privacy is valuable to everyone, precisely because it creates the conditions for everything else we value: free thought, free speech, free markets, and progress.

The Conditions for Progress

Karl Popper thought that progress was dependent on criticism. Bold ideas must be proposed, tested, and corrected, so that errors can be identified and discarded. This process requires freedom from punishment for proposing bold ideas before they’re tested and which risk being wrong. The panopticon ensures that dissent is muted before it can be voiced. Innovation requires permissions and criticism gets punished - the mechanism of progress breaks down.

David Deutsch extended Popper’s insights, positing that humans are unique in virtue of being universal explainers. Our capacity to create knowledge, to understand the cosmos, and even transform them, makes us special. Yet, knowledge creation requires experimentation, and experimentation requires the freedom to fail privately before succeeding publicly. Surveillance inhibits the freedom to experiment, for when every action is observed and recorded, it suffocates creative thinking.

These are not abstract concerns. They’re the reality of anyone who has self-censored knowing their words were being surveilled. Anyone who chose not to donate to a controversial or novel cause knowing the transaction would be visible or traceable. Anyone who avoided researching a sensitive topic knowing the query would be logged. Surveillance changes behavior, that’s one of its primary functions. Sometimes, changing behaviors amounts to constraining ideas, and thus, to constraining progress.

Money as the Final Monopoly

Throughout history, freedom has depended on the tools we had to protect it.

The printing press encouraged free speech. Before Gutenberg, ideas often were chained to scribes and priests, locked behind institutional authority. The press broke the monopoly on information.

The internet broke the monopoly of geography. Ideas could now be shared across borders in an instant. Coordination became possible without physical proximity. Censorship became harder when information could route around obstacles.

Gunpowder shattered the monopoly of knights and kings over violence. A peasant with a musket could challenge a lord in armor. Power became more distributed.

Every time, a new tool smashed an old monopoly. Now, one monopoly remains: money.

Money is the most powerful coordination technology humans ever built. It’s how we signal value, allocate resources, and cooperate at scale, but it remains significantly restricted. Money is the most surveilled and the most controlled technology. Every transaction can be monitored. Governments can freeze accounts with a keystroke. Banks can cancel you overnight. Increasingly, capital controls can prevent you from withdrawing your own cash.

Arguably, your money is not yours if someone else can see every transaction you make, decide whether or not to approve it, and later even decide to reverse that decision and inhibit access.

Privacy in Markets

Free markets require privacy, this conclusion follows from understanding how markets work:

Markets aggregate information through prices, meaning that as participants make decisions based on private knowledge, prices emerge from the sum of those decisions. The mechanism functions only if participants are able to make decisions based on their private information without also revealing it prematurely. A trader who must broadcast every position before taking it will be front-run. A business that must publish every supplier relationship will be undercut. A donor who must announce every contribution will be pressured.

Any leak, even just of small pieces of information, changes the market because it introduces bias and distorts decisions. The more surveillance there is in a system, the more distortion it faces. Perfect markets require participants who can act freely on private information, which is made impossible under conditions of absolute surveillance.

Your net worth should not be a public API. Your transaction history should not be a queryable database. Your financial life should not be subject to the approval of observers. These are not edge cases or paranoid concerns, they are the baseline requirements for markets to function and for individuals to be free.

5.2 The Transparency Trap

Crypto was supposed to free us from financial surveillance, but It did the opposite.

The cypherpunks who built this movement understood the stakes at hand. They understood that privacy in the digital age would not be granted by governments or corporations, but would have to be built, deployed, and defended with cryptographic tools. Bitcoin emerged from this tradition, and it did succeed in being the first crack in the dam, proof that money could exist outside government control.

However, Bitcoin has a major flaw, it’s transparent by default. Every transaction, every address, and every balance is visible to anyone interested in looking for it. The blockchain is a permanent public ledger of all of the economic activity that has ever come across it. Satoshi acknowledged this limitation in his original whitepaper, suggesting that users could preserve some privacy by generating new addresses for each transaction. That was a weak mitigation then, and it’s developed into an absurd one now.